What did you tell us is important?

On this page

Stakeholder Consultation

Initial consultation was completed in November and December 2021 with local community sector organisations representing women and girls which provided valuable insight into whether national priorities and recommendations are aligned to local need. The key issues raised by these organisations for consideration to help inform our local Strategic Priority Objectives were:

- Support for Victims needs to be longer-term and trauma-informed, including support for historic abuse; there should always be an ‘open-door’ policy, including repeat or re-referrals

- Trauma-informed approaches should extend across the system, beginning at Primary school age

- Impact of initial response from police is key, and certain terminology used by the police such as ‘alleged’ victim can be alienating

- Challenges navigating the whole criminal justice system and the need for dedicated / specialist officers or SPOCs throughout criminal justice process to assist victims to overcome these

- Professional Complicity and perpetrators manipulating workers/systems; undermining victim confidence to disclose; need to shift responsibility from victims to reduce their risk / seek help

- Unique vulnerabilities of those living in rural and other isolated communities

- Need for wider cultural change in attitudes to challenge behaviours from a young age

- VAWG does not just happen at night-time and not just in public places.

These organisations also helped us ensure we used a person-centred and trauma-informed approach wherever possible to seek feedback from with those that are at risk of and/or been subjected to VAWG through supported focus groups and online survey questions.

Regular meetings were held throughout February and March with strategic leads within North Yorkshire County Council and the City of York Council, alongside North Yorkshire Police, North Yorkshire Fire and Rescue Service, Yorkshire and the Humber Probation Service, and NHS North Yorkshire and Vale of York CCGs culminating in a co-production workshop to further develop the proposed scope and strategic priority objectives. This also highlighted the need to ensure consistent language and terminology is adopted, the importance of joining-up this Strategy with other relevant multi-agency strategies and the need for additional targeted consultation from other under-represented women and girls such as those in care and Care Leavers.

Victim and Survivor Focus Groups

Six Victim and Survivor focus groups were held in February 2022 with approximately 30 individuals who were willing to share their expertise by experience. Participants provided specific feedback on our proposed Strategic Priority Objectives and key areas of work across a number of themes which are outlined below.

Language and Terminology

The focus groups were specifically asked whether they had a preferred descriptive term such ‘Victim’ or ‘Survivor’, and if there were any terms or words we should never use. Some women felt they needed to use the term ‘victim’ to be heard by services, and even family and friends to recognise they need help or support, whereas ‘survivor’ might imply that the abuse is in the past and no longer has an impact. However, some women felt empowered by being a ‘survivor’ compared to a ‘victim’ which might connate vulnerability. Ultimately, all focus groups agreed that individual experiences of VAWG are varied and often ‘fluid’ and the appropriate term will depend on where each person is on their own individual journey to recovery.

The focus groups highlighted the importance of using non-judgemental language and questions; examples provided of judgemental language included when victims were asked “why did/didn’t you…” as this infers blame on their part, as well as demonstrating a lack of understanding of abuse and trauma responses. Similarly, we were told that asking someone to tell their “story” suggests that the experience they are recounting could be made-up. As a result, we have drafted this Strategy and all accompanying documentation using non-judgemental language wherever possible and will ensure this is adopted within any training packages and awareness raising campaigns.

Proposed Scope of the Strategy

As a result of feedback from the focus groups, ‘Breaches of Protective Orders’ was added as a separate VAWG type included within the scope of this Strategy as it was raised that whether these can be evidenced and therefore any breaches enforced effectively disproportionally affects women. This was an issue raised by several participants across all the focus groups that protective orders did not always fulfil their purpose to protect them from further harm, primarily as the burden of proof that a court order had even been issued remained with the woman to provide evidence of both the order being granted and effectively served on the perpetrator. It was felt that some breaches of a protective order were not always taken seriously, as the actions in question may appear to be relatively minor if taken in isolation. ‘Project Shield’ (detailed at Appendix C) is a pilot that has taken place to record all Non-Molestation Orders issued by the courts for victims in North Yorkshire and the City of York on the Police National Database, to allow North Yorkshire Police officers to confirm if an order had been issued and served to the perpetrator to help them more effectively enforce any breaches and ultimately better safeguard victims from further abuse.

Additional key partners and settings were also adopted into this Strategy following on from suggestions from the focus group including legal professionals such as Solicitors, Magistrates, Judges and Court Staff; Workplaces and employers; Nurseries; and Sports clubs and Communities.

It was noted that all the focus groups felt more training on VAWG is needed across a wider range of professions to be able to spot the signs and to know how to respond better, particularly in shifting the onus from the women to the perpetrator to make changes in their lives. This is particularly important as women can often feel retraumatised by an inappropriate response. Several of the women highlighted the importance of women and girls who have been subject to violence being directly involved in the delivery of training, and how powerful this could be in providing an authentic voice.

Proposed Strategic Priority Objectives

All Strategic Priority Objectives carry equal weighting, however following feedback from the focus groups ‘Listening to All Women and Girls” was made Objectives 1. The consultation that has taken place so far has been vital in shaping this Strategy and pro-active consultation will continue throughout the lifetime of the Strategy to ensure that the voices of women and girls remain central. The focus groups also reiterated the importance of consulting with women and girls with disabilities including neurodiversity’s and Trans women.

Prevention and Early Intervention to tackle the root causes of VAWG

The consensus was that this is fundamental to breaking generational cycles of abuse and that a Public Health approach should be adopted, focusing on challenging sexism and misogyny from an early age.

The women in the focus groups felt that Clare’s Law should be used promoted more widely to increase awareness of this as a preventative tool.

Increasing Public Confidence and Strengthening the Multi-Agency Approach to Address VAWG

A number of women participating in the focus groups questioned how trust and confidence can actually be improved based on their personal experiences and it was suggested that the only tangible way to improve confidence across the system would be to increase the number of successful prosecutions in VAWG cases. Initially ‘Increasing Public Confidence and Trust in the Police’ and ‘Strengthening the Multi-Agency Approach’ was a joint priority, however, as a result of the feedback received, these have been split and become priorities in their own right. Increasing Public Confidence and Trust in the police will allow focus on improving the initial response and ensuring the right support is offered by police officers and staff to victims. Strengthening the Multi-Agency Approach will allow exploration of opportunities to improve the experiences of those who have reported VAWG offences at various points of their journey through criminal justice process.

Experiences of reporting to the police were varied and although some women praised the responses and support offered by some individual officers there appears to be an inconsistency of knowledge and/or attitudes towards victims, particularly those reporting non-violent incidents. There were mixed views on the gender of officers, but a number of women did feel that male officers responding to a call is not always appropriate depending on an individual’s circumstances or experiences.

Some women reported that the police would be ‘the last people they would turn to for help’ as based on previous experiences reporting incidents to the police, they didn’t feel like their concerns were being taken seriously and officers made them feel “blamed” or “gaslighted” that it was their fault, and that they were often treated as “a statistic” rather than an individual. A number of women agreed that it feels like the burden of proof often lands with the victim to prove their account is true and felt officers don’t fully understand the impact of and responses to trauma, particularly around trauma-bonding between a victim and a perpetrator. Some women suggested they should be able to request a 2nd opinion from a different police officer if they do not feel believed or feel blamed or judged for their action or ‘inaction’.

Some women reported that it was not clearly explained to them what would happen and when, particularly in the early stages after initial reporting when there was ‘such a whirlwind of actions’ but they did not know about next steps or potential timescales involved. Examples of this included not being prepared for the level and detail of personal, sensitive questions they were asked, often having to repeat these details to multiple officers involved in their case, and a case where a victim’s mobile phone was taken in as evidence and was not returned for a significantly long time, which was in itself quite ‘triggering’ and disempowering.

Others reported that they felt the police did not respond to requests for updates or contacts in a timely manner, and that information is not shared effectively across the organisation. Some women also reported that they felt the onus was on them to be responsive to requests for further information or follow up contacts by the police, and there appears to be no consideration of when they are available to talk. Some women reported being called by the police whilst at work or other inappropriate situations to be able have a private conversation. One woman also reported feeling panicked when she was asked to come back into the police station to make a further statement as she did not have anyone to look after her children.

The majority of women agreed that having to repeat their experience/statement/account over and over was exhausting and re-traumatising, and some women suggested that a way to improve on this would be a dedicated or central team who know or able to access the details of all cases to be able to provide regular updates and spare victims from having to repeat their experience multiple times to different individual officers. A further view shared by the majority of women was that they are expected to take action to protect themselves and their children such as changing their behaviours, social media activities and even moving house in extreme cases. It was also raised that the police should be more aware of disabilities and provide information in Easy-to-Read formats.

Some of the women who reported that their experience with the police was positive, then felt let down by the CPS and court processes if it progressed to trial. The most common issues reported with the wider criminal justice processes was in respect of delays in cases being brought to court which can result in cases being ‘No Further Actioned’ and protective orders not being issued immediately, meaning breaches are not enforced effectively.

Again, a number of women reported that they were not given clear information about what would happen and when throughout the process. Notably it was highlighted by some women that the whole criminal justice process feels driven by the defendant i.e., hearings are postponed if the defendant does not appear which some women felt was a tactic used by perpetrators to re-victimise them further by drawing out the who process and increasing the likelihood of them retracting their statement.

The court process and environment overall were also described as being traumatising not only due to the fear of seeing the perpetrator in person, but also a number of women felt they were further victimised through ‘character assassination’ and if a woman becomes upset or emotional when testifying, it was felt that this was held against them with one women reporting she “felt chewed up and spat out by the system”. Some women also highlighted that jury members do not have a good understanding of non-violent crimes and are not always provided with appropriate information to help them understand more complex issues such as coercive controlling behaviours and modern slavery.

Specific mobility and accessibility issues were also raised by some women, both in terms of the physical accessibility of court premises and facilities and the lack of information being consistently available in different formats or languages. An example was provided where a hearing-impaired victim was offered special measures to have screens when giving evidence, but this meant they would be unable to lip read which is their primary means of understanding others.

Another common issue raised at the focus groups was that the criminal justice system as a whole feels disconnected and information-sharing between agencies is not effective which left victims having to repeat their account on multiple occasions. The process of going through the criminal justice system was described as “a full-time job” by one woman as she felt had to link-up the range of agencies herself to ensure they all had the correct information, with another agreeing that “it was hard to compartmentalise all the different agencies that are involved in the system” and their different roles and responsibilities. The consensus was that if different agencies were better linked up with improved information sharing and consistent approaches to updating victims, this would make for a more trauma informed system and reduce the risk of victims withdrawing from the process.

Enhanced Support Services for Victims

Overall, the focus groups shared significant positive experiences of support provided by IDAS. It was felt however that support should be offered at multiple and different stages, recognising that victims may change their mind and want to take up support after initially refusing, but may feel they ‘have missed their chance’. Furthermore, it was felt there was a lack of awareness of the different support services available and what each service offers. A centralised victim-focused single-point of information and access is available, so further promotion of this is required, as is the need to ensure that victims are offered or sign-posted to these services in all cases.

A sense of unfairness was conveyed by some women in respect to victims’ rights to legal help and advice compared to the rights of perpetrators, for example it was highlighted that a perpetrator is offered a solicitor as soon as they are arrested, but the same does not apply to a victim. Some women also asked why North Yorkshire Police no longer use the National Centre for Domestic Violence (“NCDV”); a number of women reported they found NCDV to be helpful in obtaining a Non-Molestation or other protective order, and that women should be equipped with the relevant information to be able to make a choice of who to use and felt it didn’t matter if solicitors were local or not; some women shared they felt let down by local solicitors.

Post-court support was highlighted as lacking, and a number of women felt that more support should be offered immediately after the court hearing “even if it is just a safe space to have a cup of tea and a cry”. The need for more availability of longer-term post court trauma support/therapy was also highlighted, alongside the lack of support for family members/new partners to help them better understand the impact on the victim and their behaviour as a result.

Supporting Behaviour Change for Perpetrators

The focus groups on the whole did not agree that perpetrators should be ‘supported’ as they felt there was already unfair focus on perpetrator needs. Some women did agree that more work is required to challenge perpetrators and make them change their attitudes and behaviour, and that the responsibility should be shifted to perpetrators to stop their behaviour rather than expecting women to change to protect themselves from perpetrators.

However, the women involved in the focus groups also expressed some cynicism around the ability of perpetrators to genuinely change their abusive behaviour and felt that perpetrators were often skilled in the manipulation of systems and creating professional complicity.

Awareness Raising

The consensus from the focus groups was that flyers and posters in isolation aren’t effective in engaging people, we should utilise as many forms of communication as possible to catch everyone both online and in public places such as buses, bus stops and cinemas.

The focus groups agreed we should be aiming high for wider societal change such as challenging stereotypical attitudes in public organisations such as the police and fire service and military which will have a ripple effect into wider society. Another suggestion was to secure a ‘Brand Ambassador’ – well-known local community leader or celebrity who have personal experience e.g., Mel B recently spoke out about her experiences of domestic abuse.

It was suggested we consider how to better engage with local and even national journalists and media outlets who often ‘victim blame’ and perpetuate sexist stereotypes and attitudes.

Many women felt having women and girls who have experienced VAWG directly involved in raising awareness and training packages provides a more credible voice, and as a minimum we should include case studies of real people and real experiences. ‘The Voice’ training package by Rachel Williams was recommended as a trauma informed engagement approach.

A social media campaign that focuses on positive behaviours and attitudes rather than highlighting negatives was suggested to support wider engagement such as ‘Be Proud to Respect Women’ as VAWG needs to be deemed unacceptable by men as well as women. It was suggested that online dating sites could play their part in raising awareness by having information available for all to be aware what abuse looks like and signpost to links for help and support. However, it is important to remember that perpetrators can and often do monitor online and social media activity.

Raising awareness of VAWG in schools and colleges was seen as integral to challenging inappropriate behaviours and attitudes form an early age, and it was felt work could be done with staff in settings such as nurseries and to be aware of the signs and how to link parents into support if appropriate.

Copies of this VAWG Strategy should be available to read in public places such as GP surgeries and libraries and be available in different formats including Easy-to-Read.

Telling Someone

There were many and varied individual reasons why women didn’t tell anyone about the abuse they had been subjected to, but the most common themes were not recognising themselves as a ‘victim’ particularly when the abuse wasn’t physical; the prospect that they would not be believed; and fear of repercussions from the perpetrator, particularly where they shared children.

Girls and Younger Victims

The North Yorkshire Youth Commission contributed to the consultation. The Youth Commission are a group of young people aged between 10-25 who inform, support, and challenge the work of the Police, Fire and Crime Commissioner, North Yorkshire Police and North Yorkshire Fire and Rescue service. The Youth Commission members were most interested in seeing tangible and practical solutions that offer immediate improvements.

Examples included stronger policing of the Night-Time Economy, working in partnership with bars and clubs, providing ‘spiking’ test kits: There’s an extraordinary amount of spiking that goes unnoticed because people are too embarrassed, so crimes go unpunished.” more street-lighting, and an overall higher police presence. Men and boys’ mental health support was also highlighted as a vital part in ending the cycle: “Girls and women’s safety should always be a priority, not just when someone has died at the hands of a man.”

We also consulted with The Children’s Society to consider the findings of national consultation and reviews they had conducted to ensure we were still considering the views and experiences of girls and younger victims of VAWG in developing our local responses and support services.

Missing the Mark (2020) research of young people experiencing teenage relationship abuse found that:

- The impact and scale of domestic abuse that children and young people experience within their own intimate relationships is often overlooked

- Many under 16s are both likely to have experienced domestic abuse and struggled to access services

- Terms such as ‘domestic abuse’ and ‘intimate relationships’ lead to certain preconceptions about what situations of domestic abuse may look like and correspondingly impacts on how victims of domestic abuse are identified and what responses they are offered. These preconceptions do not always fit with the situations of violence and abuse in relationships experienced by young people. For example, abuse in teenage relationships do not always involve the victim and the perpetrator regularly sharing the same ‘domestic’ setting

- Professionals’ biases about what a typical intimate relationship may look like, can result in missed opportunities to identify abuse in teenage relationships and the correct response is therefore not given

- Due to the lack of clear national guidance on the issue, abuse in teenage relationships is often not addressed through early intervention, allowing situations to escalate

- Young people are often coerced and controlled through the introduction to or the use of substances. Alcohol or drugs can desensitise the ‘problem’ for the victim and the capacity of the victim will fluctuate as a result of the substance misuse, which may be forced by the perpetrator

- Teaching children about healthy relationships, whilst important, on its own is not enough. Young people might feel confident recognising they are in an unhealthy relationship, however exiting the relationship is a different matter. Young people must be provided with robust and long-lasting education about domestic abuse including recognising that it can occur online and be given practical tools to aid with conflict resolution. They should feel empowered to ask and know where to ask for help if they recognise that a relationship, they are in is not healthy

The Children’s Society response to a VAWG Call for Evidence (2021-2024) was informed by national practice and research as well as a consultation exercise with practitioners across their projects which surmised that:

- VAWG can happen to anyone irrespective of their age, race, culture, sexuality, or class. However, some factors in a child’s life, such as previous experiences of abuse or domestic violence at home, poverty, and inequality of opportunities in their communities can make some young people more likely to become victims of gender-based violence. Systemic issues, such as insufficient support for children in the care system and immigration system can also make girls and young women more likely to experience VAWG

- VAWG is often perpetrated by people girls know, family members or someone within their social circle. In recent years peer on peer violence both in relationships and in group/gang contexts are reported to have increased. Increase in female-on-female violence has also been reported. Online facilitated VAWG has also increased, particularly during Covid-19, with the age of children affected getting younger

- Whilst practitioners highlighted many ways that social, cultural, and structural factors make girls more vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, they also reflected on violence experienced by young males, LGBTQI young people suggesting that the national strategy needs to address a wider set of issues.

- The existence and experience of violence and abuse for the young people across genders has become normalised for many young people, particularly where it is linked to earlier or current experiences of growing up with violence and domestic abuse at home. As a result, young people are often not able to identify their experiences as violence, exploitation or abuse or their behaviour as violent or abusive

- Many young people don’t have any good reference points for healthy and consensual relationships and girls almost seem to accept violence as part of normal relationship or interaction with a male

- Time-limited interventions that often stop when the young person is starting to develop their trust in professionals are not seen as helpful or even ethical. ‘Firefighting’ was a term often used to describe current commissioning of support services for girls

- There is an overreliance on girls and young women disclosing crime. More emphasis should be put on agencies proactively identifying girls and young women at risk of VAWG and disrupting VAWG as early on as possible. There is a need for a greater awareness among all safeguarding agencies about the impact of VAWG on girls and young women and the signs that professionals should be aware of to identify girls at risk. Legislative changes such as introduction of a new offence focused on coercion and control of children can help with ensuring that professionals share the same understanding of coercive control and have tools to disrupt it

- The scale and level of sexual offending against children and young people makes it paramount that children and young feel confident in disclosing crimes and seeking help and that perpetrators of these horrific crimes are left in no doubt that the criminal justice system is on the side of the victim

- Young people’s experience of police is not always related to their experiences of reporting an offence against them. Many young people come into contact with police in a variety of situations – from day-to-day contact on high streets and public transport to being found after the missing episode. Research highlights that children’s overall impression of the criminal justice system could be largely influenced by their experience with the individual police officer that they saw. If those day-to-day contacts and experiences are not positive, it may be more difficult for young person to trust police when they become a victim of a sexual offence

Online Survey

In order to ensure everyone was given the opportunity to have their views represented, an anonymous online survey was available and open to everyone – of every gender, every age and every situation – for approximately 4 weeks in March 2022. The survey was promoted using social media to direct respondents to the OPFCC website and survey link with nearly 30,000 people reached overall through the social media campaign.

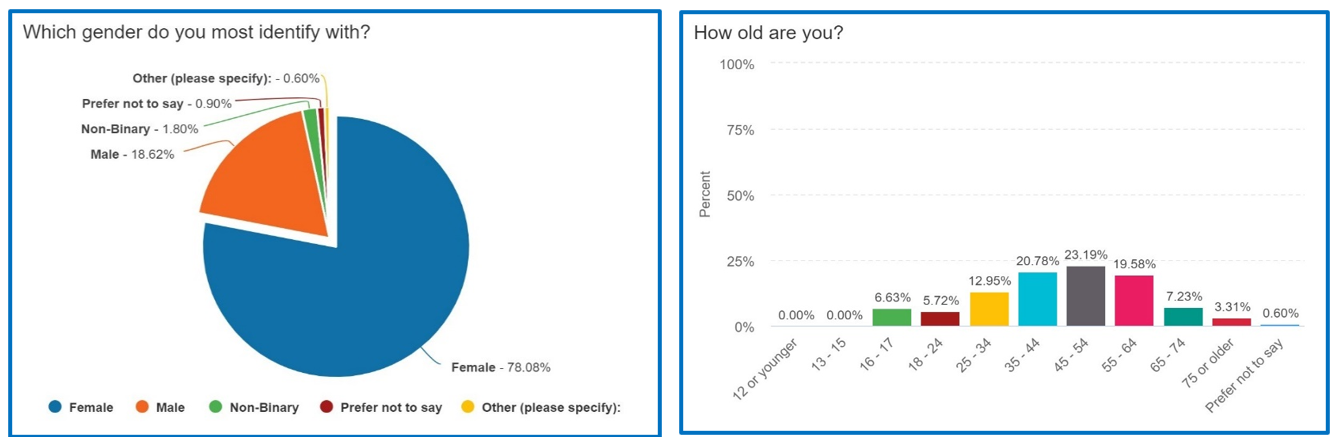

Over 800 people came to the survey, with 332 completing the survey. 80% of the data collected was from females. 12% of respondents were under 24yrs old and 31% were over 55yrs old (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Age and gender profiles

Base: All respondents; n=332

The data further identified that 14% of all respondents were from the LGBTQ+ community. This is above the national average of 6% of the population that identify as LGBTQ+ and the local average of 6% according to ONS1 from 2019 (most recent data available).

Language and Terminology

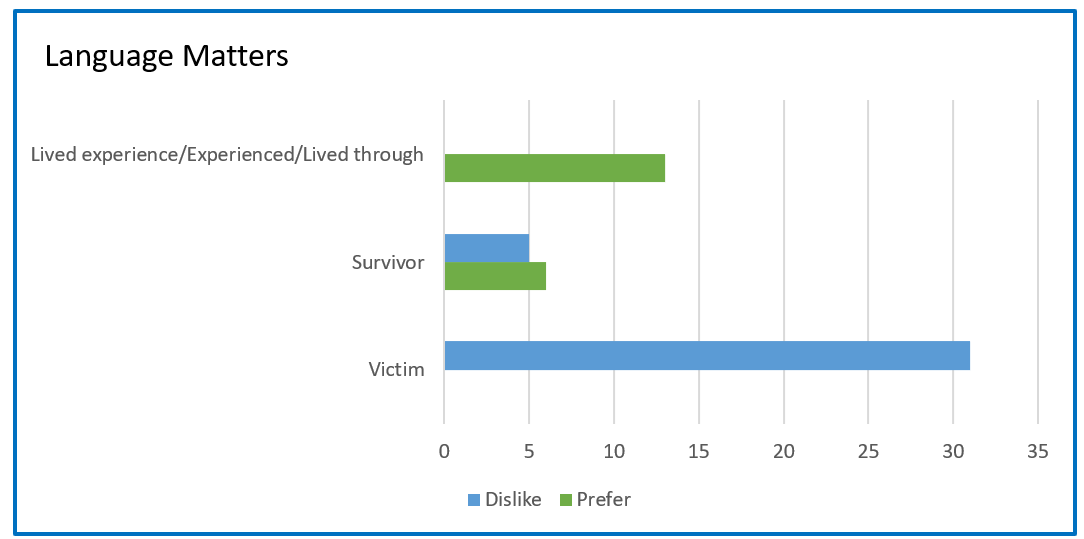

The terms ‘victim’, ‘survivor’ and ‘lived experience’ (figure 2) were the most commonly identified terms. Over 50% of respondents did not like the term ‘victim’, but there were limited alternatives for other terms suggested.

Figure 2. Use of language

Base:Those who responded, n=55 of 64

Question: Are there any particular words/phrases/use of language that you are not comfortable with, and we should never use?

Although the term ‘victim’ is not preferred by all, the majority of respondents understood that the term was the most recognisable. Respondents also stated that they understood most terms do not aim to do harm, and as quoted below, when engaging with and supporting anyone who have experienced any kind of abuse, it is essential to empower that person by asking them what they would prefer.

“I recognise that those who have been a victim of male violence may not appreciate being labelled with those terms. I think it’s really important to listen to those individuals and use terms which empower women and put the responsibility back onto the perpetrators.”

“Personally, as a survivor of sexual abuse I find the word ‘victim’, less empowering, however I am acutely aware this is a personal and other individuals I have met who have been sexual abused relate more to the word victim.”

Therefore,zzx this Strategy will use the term ‘victim’ as the most universally recognised term, however, it will be recommended that services that interact with victims ask their preference of terminology when establishing initial contact.

Proposed Scope and VAWG Types

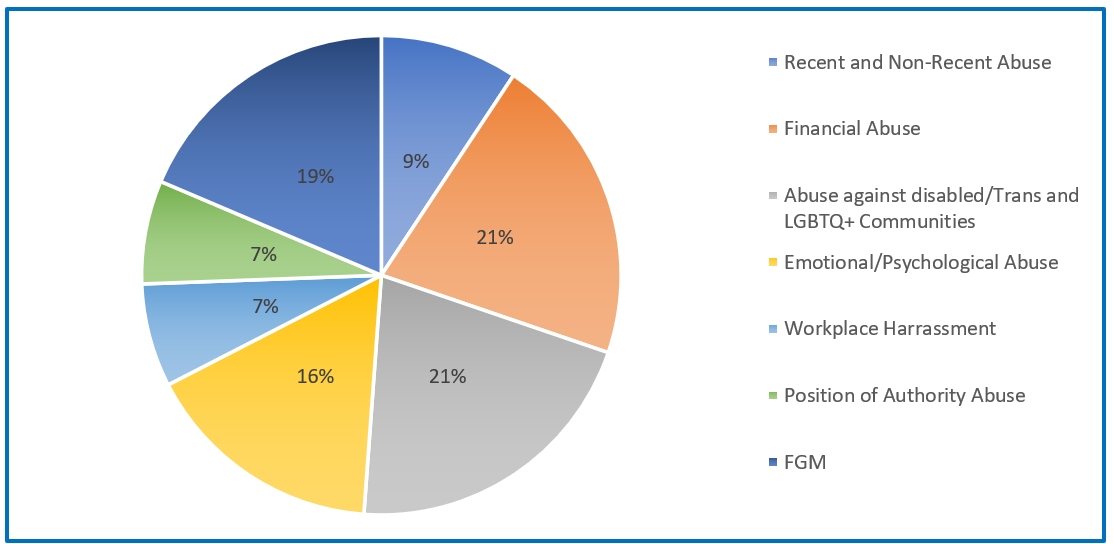

To identify any possible gaps within the proposed scope of this Strategy and strategic priorities, the survey asked about what respondents thought we might be missing (figure 3).

Figure 3. Areas missing from local strategies

Base: Those who responded: n=43 of 74

Question: Do you think anything is missing from this list? (Yes/No) If yes, what have we missed?

22% of respondents identified the areas they felt were missing from the proposed scope, in figure 3, however they are in fact included and can be found in the more detailed list at Appendix A. Moreover, with 78% of respondents confirming we had missed nothing, this confirms the work we have done so far has been an accurate reflection of what is needed locally to help address VAWG in North Yorkshire and City of York.

When asked the question Please tell us about anything that you think should NOT be in our strategy? 8% of respondents suggested areas such as: misogyny, as it is not a crime; the term ‘violence’, as respondents felt it suggested only physical violence; and work that ‘victimises’ sex workers and could essentially put them in more danger.

Misogyny: the UK government has recently (Feb 2022) decided to reject calls to make misogyny a hate crime, based on a Law Commission report which warned that extending hate crimes to cover misogyny would prove “more harmful than helpful” to victims of VAWG. However, North Yorkshire Police, along with only 3 other forces in the UK, include misogyny as part of our hate crime recording and have done so since 2017.

Violence: although the word here for some respondents indicates some form of ‘physical’ violence, this is not a true reflection of the word, and all the areas included can be found in the more detailed list at Appendix A.

Victimising Sex Workers: in 2019, North Yorkshire Police adopted sex workers into official policy for tackling and dealing with hate crime and use this for recording and monitoring as a means of protecting vulnerable individuals and encouraging reporting of crimes against them.

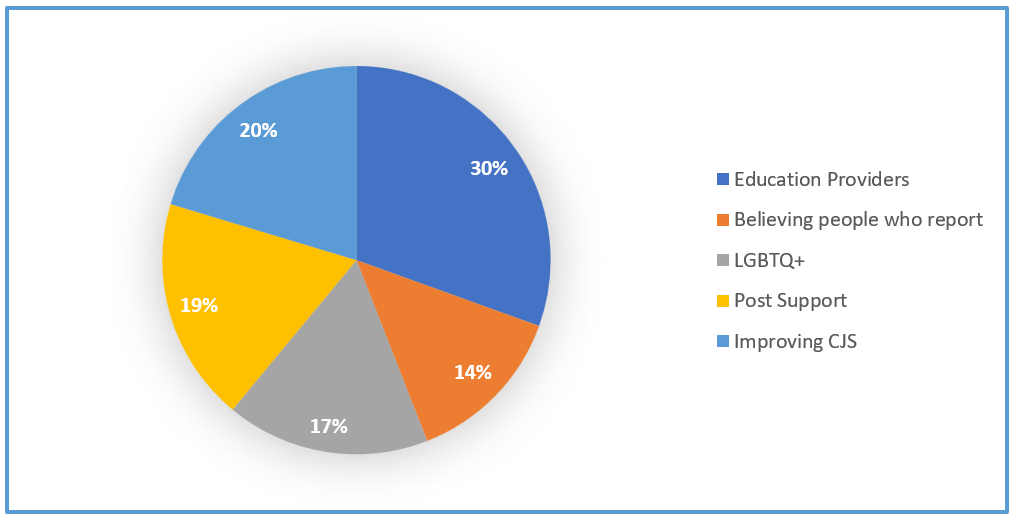

When looking at identifying missing areas from the national strategies the areas in figure 4 were identified and these should be considered locally.

Figure 4. Areas missing from national strategies

Base: Those who responded: n=94 of 332

Question: Do you think anything is missing from this list? (Yes/No) If yes, what have we missed?

72% of respondents said there was nothing missing however of the 28% that suggested areas of concern around improving post support services and being inclusive and listening to voices from all communities, which we do already include in local work and is one of the proposed priorities of our strategy.

“Please ensure that “Improving support for women and girls, particularly those from under-represented communities” is inclusive of trans women and girls.”

“The specialist support for women and girls from minoritized backgrounds is key. By and for support is crucial. Also, possibly something to do with support being prioritised – reporting is often re-traumatising and usually the outcome is an NFA – women and girls need to know that they do not have to report to the police and support services are still available irrespective of this.”

Delivery Approach

In the next section we asked for thoughts on agencies to be included in partnership working and had suggestions from 35% of people to include:

- Nurseries/Child minders

- Male dominated hobby places/clubs (e.g., football, sports, pubs/clubs)

- Youth-related agencies

- Citizens Advice

- Housing

- Immigration

We will aim to include representatives from these areas of work moving forward to develop our local delivery plans.

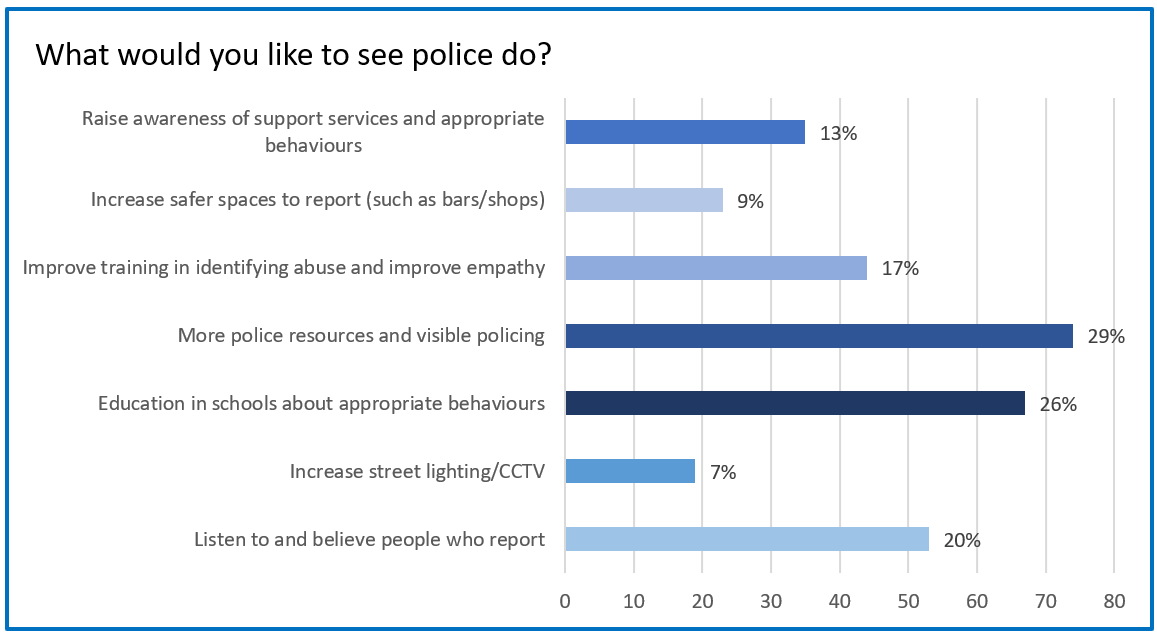

Police Response to VAWG

North Yorkshire Police’s response to people who report VAWG crimes is key to ensuring public confidence and trust in their ability to effectively tackle VAWG. Similar to national reporting trends, reporting of VAWG related crimes are low.

We asked what police can do locally to tackle VAWG, and specifically what they should start or stop doing to increase reporting of VAWG crimes.

Figure 5. Ways police can tackle VAWG locally

Base: Respondents: n=260 of 332

Question: Is there anything that the police can do locally to tackle Violence Against Women and Girls? Yes/No Please tell us about what you would like to see being done locally?

As can be seen from figure 5, 78% of responders contributed to this area and the biggest proportion of those identified that having more police resources; education in schools; and ensuring people who report VAWG crimes are listened to and believed are the most important things the police can do locally. These accounted for 75% of responses. However, there was also a large number of respondents who understood that many of the issues identified were complicated.

“Better understanding across the force of how to be supportive of domestic abuse victims. The pursuit of getting statements is at times relentless and does not seem victim led. We know it’s important from a police perspective to gather evidence but listening to the victim’s voice is vital.”

“Training needs to continue throughout all departments. Training around consent, healthy boundaries, emotions, and trauma responses. There is more of a demand for these subjects to be understood and more informed.”

“Ensure they are thoroughly explaining processes to victims of crime, speak to them as human beings and be compassionate that their life has been affected by the crime… if not going to be investigated or taken further, explain thoroughly why not but also highlight they have been recorded correctly.”

“It’s tough for the police, they have become first contact practitioners. Probably not the role they thought they were going to do. look behind the behaviour, what are you not being told.”

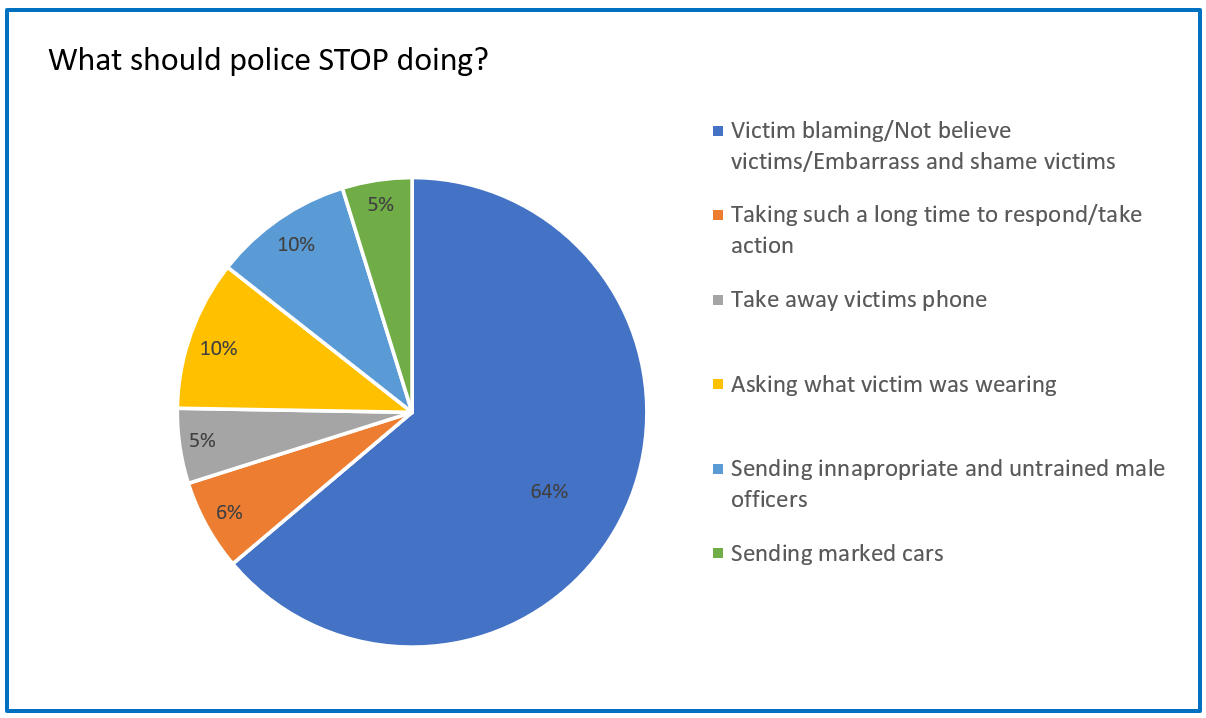

As can be seen in figure 6, the data identified the common barriers to reporting aligned to the national findings, with a substantial 64% of respondents stating that the police victim blame, do not believe them and/or embarrass or shame those reporting. All themes pulled out from the data can be addressed through appropriate training, disciplinary actions and overall cultural change within the force which this Strategy will prioritise.

Figure 6. Things police can stop doing to improve reporting

Base: Respondents: n=299 of 332

Question: Thinking about what would make you reluctant to report an incident, what should the police STOP doing when women and girls report violence they have experienced or witnessed?

When asked what police need to start doing, these were in the main the opposite of those things they should stop doing in figure 6 above. In addition, there was one suggestion about finding easier ways to report, such as an online form; North Yorkshire Police do currently have several ways of reporting, including online forms through the Single Online Home so awareness and promotion of these reporting routes needs to increase. For other areas of improvement identified by respondents that we can influence, this Strategy will consider these recommendations as we implement our local delivery plans to support the police and strategic partners to increase public trust and confidence to report VAWG offences.

“There are so many barriers that come up when reporting and being believed is a massive one.”

“I would be reluctant to report incidents if I felt I was going to be judged, not listened too, feel like my character is being questioned and not believed.”

“Treating the victim as a suspect… Let’s be more proactive in getting that first account right… It’s the most important part of the initial investigation and helps build trust between victim and the police.”“Asking them if something “really happened.” Constant and continual requests for information/ evidence Telling women they may get into trouble if they report something “false” or “waste police time”…”

“Questioning their feelings, views, and accounts so that victim’s feel they are at fault or being investigated. Dismissing information which helps to build a whole picture of the abuse as irrelevant. Making inappropriate comments about the victim and their experiences so that they feel the abuse was their fault.”

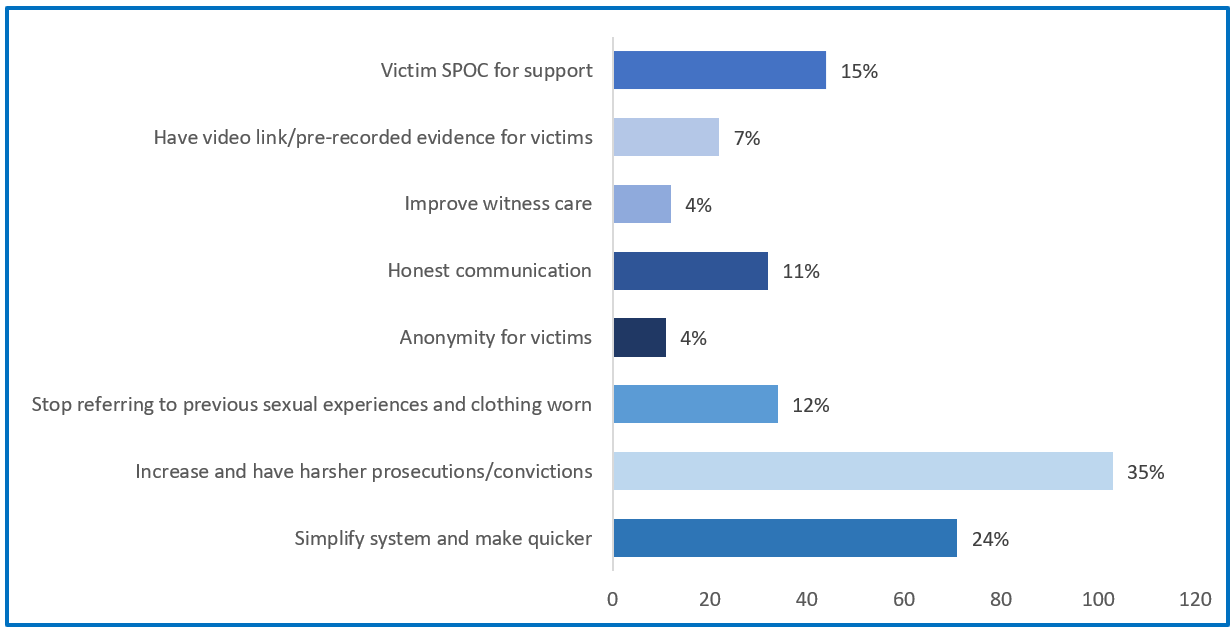

The Wider Criminal Justice Response to VAWG

The wider Criminal Justice System (“CJS”) including the Crown Prosecution Service and courts are another area which directly influences the public confidence around reporting VAWG crimes. Within this Strategy we wanted to identify what could be done by the wider CJS agencies to better support police in increasing confidence for victims, figure 7.

Figure 7. Ways CJS can support police

Base: Respondents: n=294 of 332

Question: How can the wider Criminal Justice System support the police and help women and girls to feel more confidence in the system?

89% of respondents contributed to this question with 59% stating that the CJS need to simplify the system; increase prosecutions; and give out harsher sentences.

Other identified gaps and recommendations include honest communication about timelines and what to expect to happen when: a dedicated case-building division; and dedicated court-based victim SPOC.

“A case building unit that can assist police officers in file preparation – going to CPS for charging decisions etc. These case building colleagues are very well skilled in file preparation who can complete this work quickly. This would ensure this work is done much quicker and to a higher standard, especially first time around. This would mean that potentially we would be able to get charging decisions much quicker allowing perpetrators to be put before the courts quicker therefore protecting victims, improving their level of safety and developing/improving confidence in NYP and our partners as we strive to deliver on this service priority.”

“By supporting and promoting women’s wellbeing and removing the culture of shame by empowering women to know when they report an incident appropriate support with be provided.”

“Perhaps juries need to be given a course in understanding the way that woman deal and process certain crimes. Woman should not be blamed for a male’s behaviour simply because they are wearing certain clothes or drinking alcohol. Perhaps courts should look at the balance of probabilities, rather than beyond reasonable doubt.”

“I believe the issue is wider than specifically the Police, it is down to the criminal justice system and CPS/courts who are failing victims by not hearing cases in a reasonable time frame, requiring unreasonable amounts of work/evidence from Police, and failing the victims to provide adequate sentencing and protection when it does get to court. Officers and Police staff are not the issue in my opinion, it is the failure of the courts that makes victims reluctant to report as it seems pointless.”

“Being more realistic in the timelines it sets for receiving/ dealing with evidence Setting expectations for how long a court case can take Robust system of updating victims about their court case Robust system of updating victims about prison release dates.”

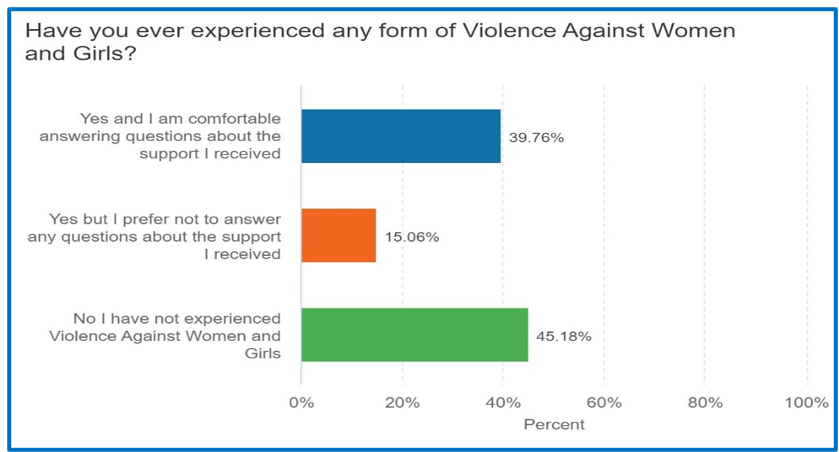

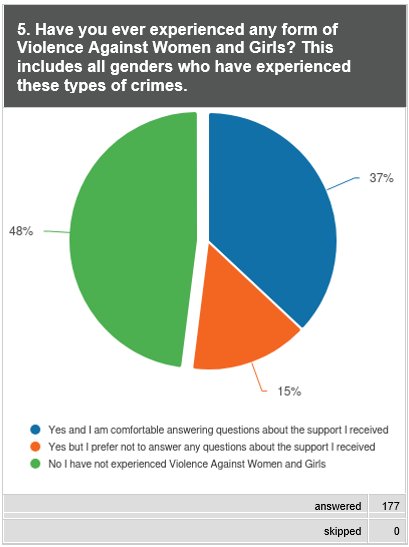

Personal Experiences of VAWG

55% of people who completed the survey confirmed they have experienced some form of VAWG as seen in figure 8.

Figure 8. Experience of VAWG

Base: All respondents; n=332

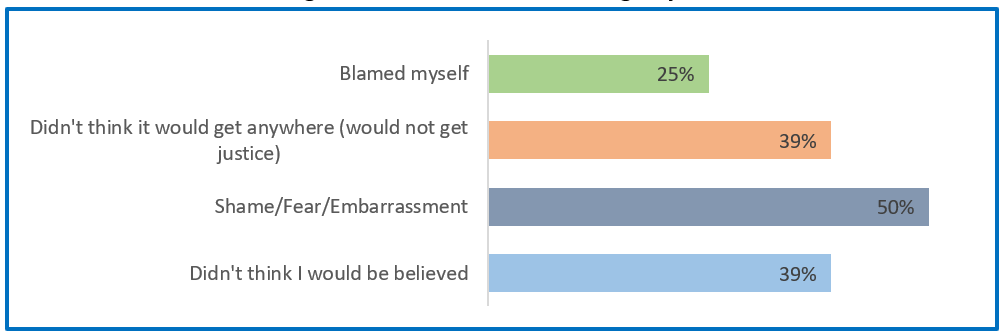

From those that had experienced some form of VAWG, 25% have not told anyone. Reasons for this are identified in figure 9 and are aligned to the barriers to reporting to the police as identified in figure 6 above.

Figure 9. Reasons for not telling anyone

Base: Those who responded: n=36 of 137

Question: Why didn’t you tell anyone?

“I felt it was my fault somehow. The person was a colleague of my father and was a married man so I thought it would cause trouble and embarrassment. I was only 14 years and didn’t really know what to do.”

“I felt ashamed that my partner was being violent and coercive towards me. It was very subtle in the beginning, so I wasn’t aware it was happening until it escalated. My stepfather was also violent towards my mother and as a child I thought it was the norm.”

“Fear of not being believed Fear that I should have told when it happened This person was a known sex offender in my area – abused another young girl who reported it, and nothing happened. I saw this in the local news, and it increased my belief that nothing would happen even if I did tell.”

“It was my husband. And I was not confident that I would be believed and scared of repercussions.”

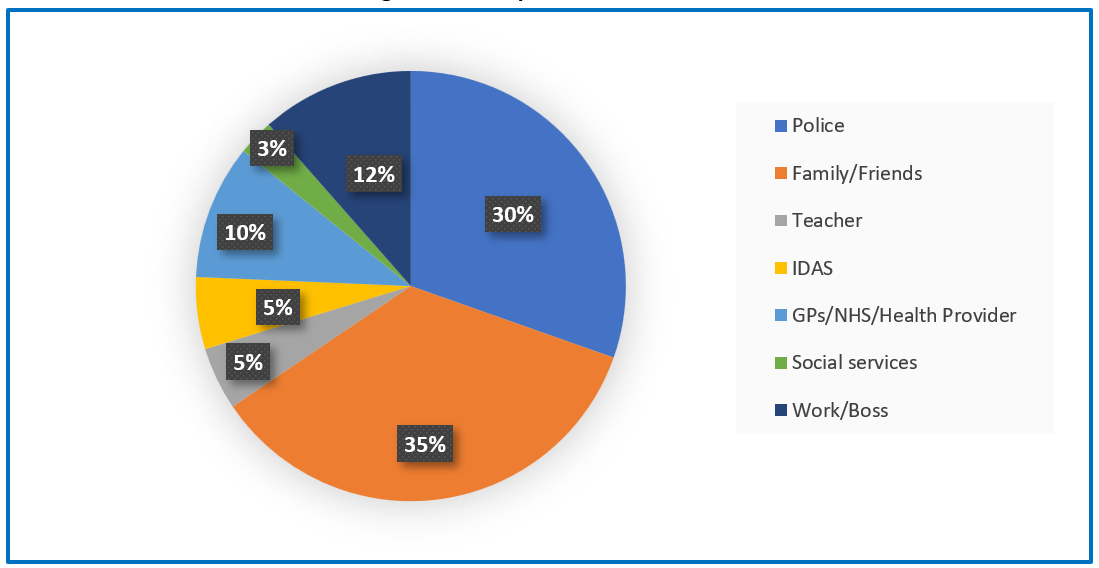

For the 75% who did tell someone, we wanted to understand who that was and how helpful their response was.

Figure 10. People who victims told

Base: Those who responded: n=99 of 137

Question: Who did you tell?

There were a number of victims that told someone at work or their boss (12%), feeling that was the easiest and most trusted person to tell. As a result, ‘employers’ have been included as key delivery partners within this Strategy.

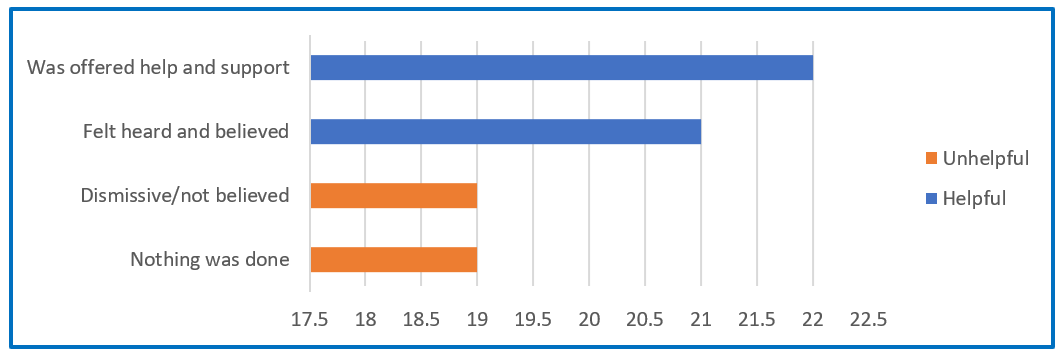

Figure 11. Response helpfulness

Base: Those who responded: n=97 of 137

Question: Was there anything particularly helpful or unhelpful about their response?

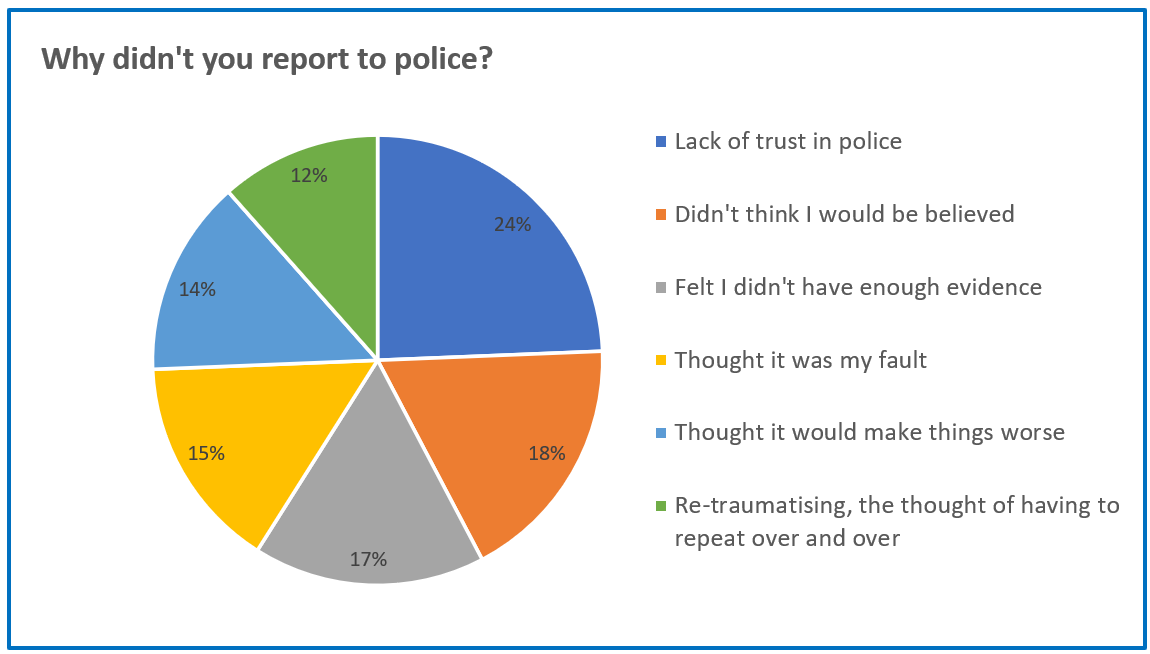

30% of victims told the police about their incident and there were a number of reasons detailed below in figure 12 which correspond to figure 9 above. This lack of trust in policing, reported by 24% of victims, is one of the specific priorities within our Strategy.

Figure 12. Reasons for not reporting to police

Base: Those who responded: n=68 of 70

Question: Why didn’t you report what happened to the police?

“Scared, felt I wouldn’t be believed, still feel I won’t be believed, afraid of the repercussions”

“I was young at the time and felt stupid that I had somehow ‘allowed’ it to happen.”

“Didn’t think they would take it seriously as a crime despite that fact that I was touched without my consent and cut without giving informed consent.”

“I think I felt to some degree it was my fault. I would not be believed, and nothing would have happened about it. I didn’t want anything to happen and dealt with it myself anyway. Also, I didn’t want to be treated in the same way I had experienced in the past – abrasive attitudes and poor standard of investigation.”

From these responses, we wanted to identify areas of improvement that we could focus on throughout the Strategy to improve overall responses identified in figure 13.

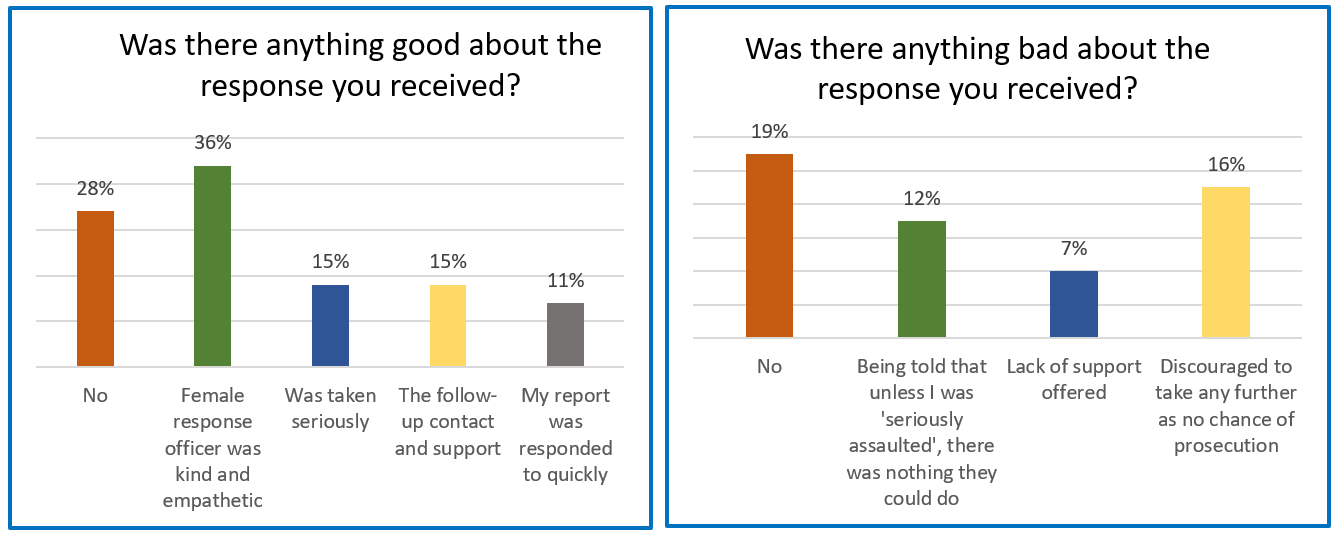

Figure 13. Good and bad responses

Base: Those who responded: n=61 of 63

Question: Was there anything particularly good about the response you received? Please say what worked well and why you found it helpful

Question: Was there anything particularly bad about the response you received? Please say what did not work well and why you found it unhelpful

The positive responses were predominantly from female officers, however 28% did not find anything helpful. 16% of respondents stated they were discouraged from taking any further action by the police, reinforcing the impact of low prosecution rates for VAWG offences.

“The officer was kind and understanding but had little in way of power to action anything to help as my word against his.”

“It was 34 years after the incident that I reported to the police. The individual call handler in NYP Control room was exceptional in her response. I couldn’t have asked for a more compassionate, patient, non-judgemental, supportive, and kind individual.”

“Very quick response, empathic and compassionate, understanding of the balance between mental health and safeguarding for the victim.”

“I had to report it into a phone at the police station as the station was unmanned. I felt scared as it was dark, and I was outside it was embarrassing as there was no privacy when I was making the call.”

“Treated as if I was a nuisance. My fears discussed as trivial. Made to feel I had overreacted One remark was “well you’re in one piece aren’t you! No harm done”.”

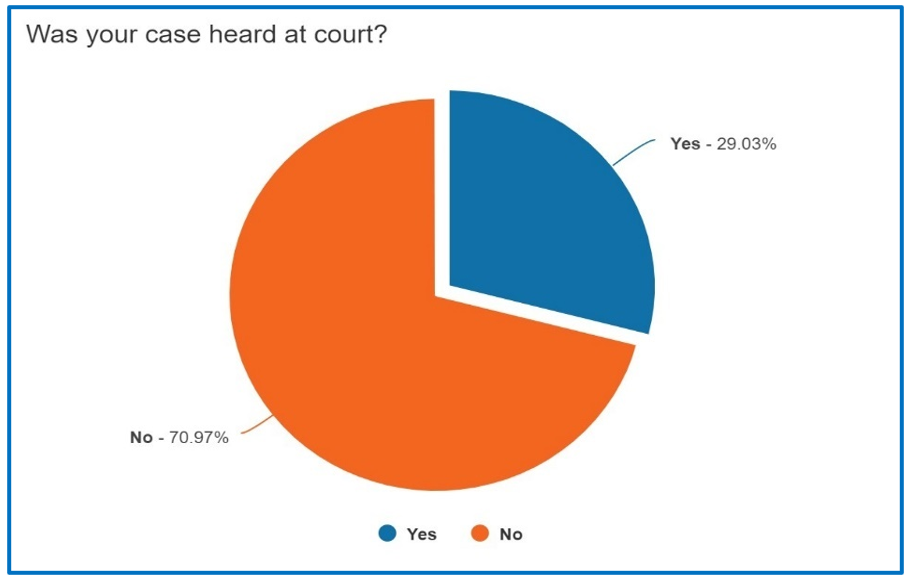

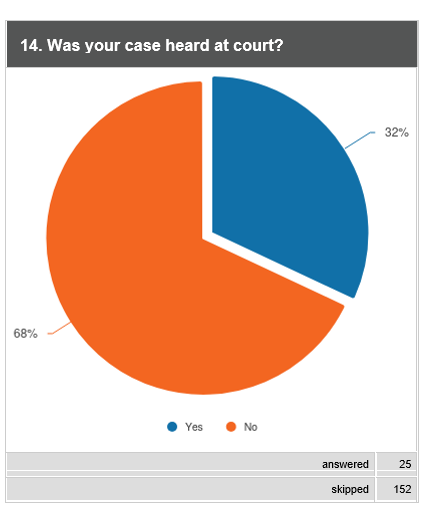

The Criminal Justice Journey

From the respondents who had reported to the police and wanted to take things further, we wanted to understand their experiences when going through the wider criminal justice processes. Figure 14 shows that 29% of those went to court.

Figure 14. Cases heard at court

Base: Those who responded: n= 63

Question: Was your case heard at court?

The reasons identified for cases not progressing to court included insufficient evidence; pressure from police to withdraw because they felt it would not have a successful conclusion, with 15% not given any reasons at all.

The predominant response from victims and their interactions with the criminal justice system identified that lengthy waiting times were the largest issue, with other issues experienced around lack of communication; insufficient witness care support; not knowing what their rights were; and having to wait in the same spaces as the accused.

“We had no support from the witness care service and the perpetrator pleaded guilty which meant we had no voice in court leaving the perpetrator to manipulate the system via his solicitor.”

“It took over a year, and £30,000 to sort out my settlement. The family court overlooked all of the abuse that had taken place. I am left struggling financially with 100% care of the children.”

“The fact that I had to go to court, there was evidence etc and he pleaded not guilty. It was only due to me being prepared to give evidence that he submitted a guilty plea upon my arrival. It felt like a further assault”

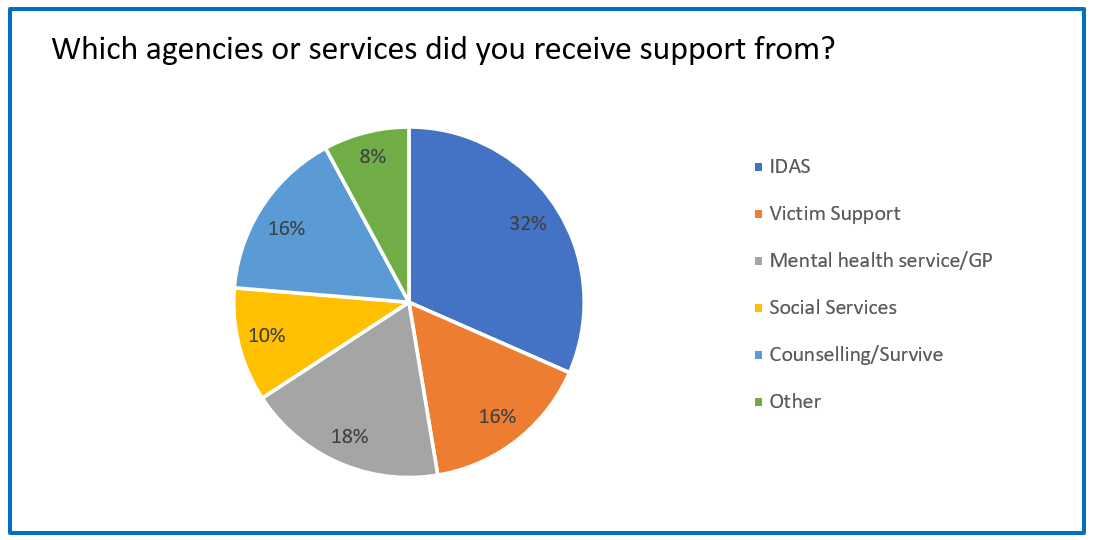

Support Services

Collectively we commission a range of support services for victims. Identifying which services were used and were most beneficial for victims is essential for informing future commissioning of VAWG support services. Of the 40% of respondents who identified as a victim, 21% received or sought further support.

Figure 15. Support agencies accessed

Base: Those who responded: n= 28

Question: Which agencies or services did you receive support from and what did they support you with?

The areas of assistance provided varied from emotional support; practical help; support with finances, housing, health/medication; and counselling that assisted with trauma management and anxiety recovery.

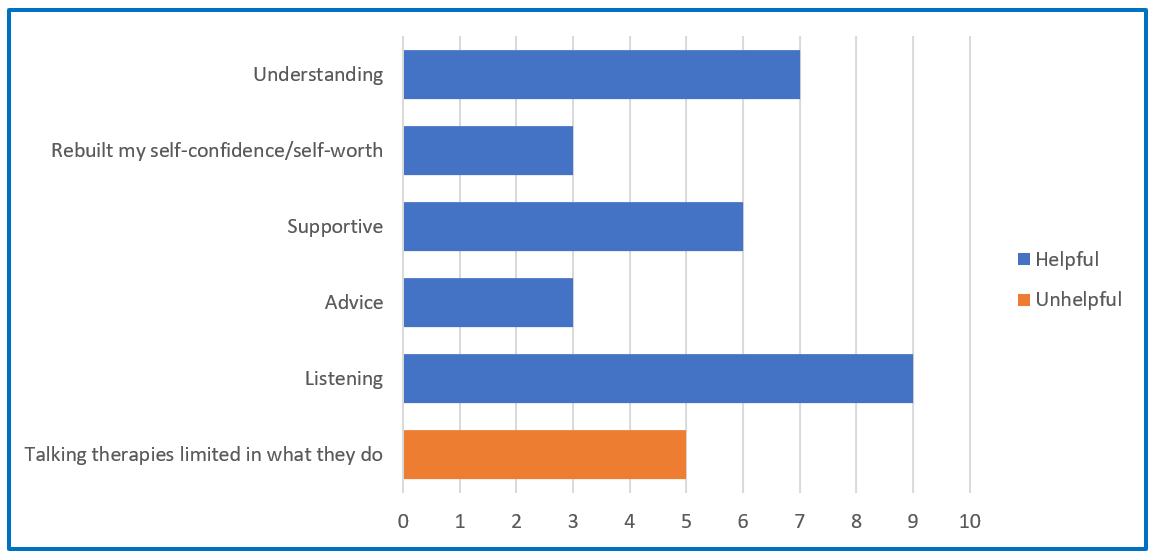

What was found to be most useful from that support is identified in figure 16.

Figure 16. Support helpfulness

Base: Those who responded: n=24 of 28

Question: Was there anything particularly good about the support you received? Please tell us what worked well and why you found it helpful

“The day that we woke up to blood on our doorstep and suicide notes. This was treated as a breach of bail rather than a separate incident of stalking. Despite us telling the police that he was on police bail they arrested him for breach of court bail and then didn’t get him to court within 24 hrs of arrest. The court then refused to hear the case”

“IDAS helped me rebuild my self-worth so that I have been able to move forward and build a better life for myself and my daughter. They listened to me and did not make me feel as if any of the abuse was my fault.”

“Finding someone that actually listen to what I was saying and understood.”

“Processing this when I was ready. Talking without being judged.”

Anything Else to be Considered?

To ensure the voices of women and girls remain central to the development of this Strategy, direct quotes from respondents have been threaded throughout this Strategy.

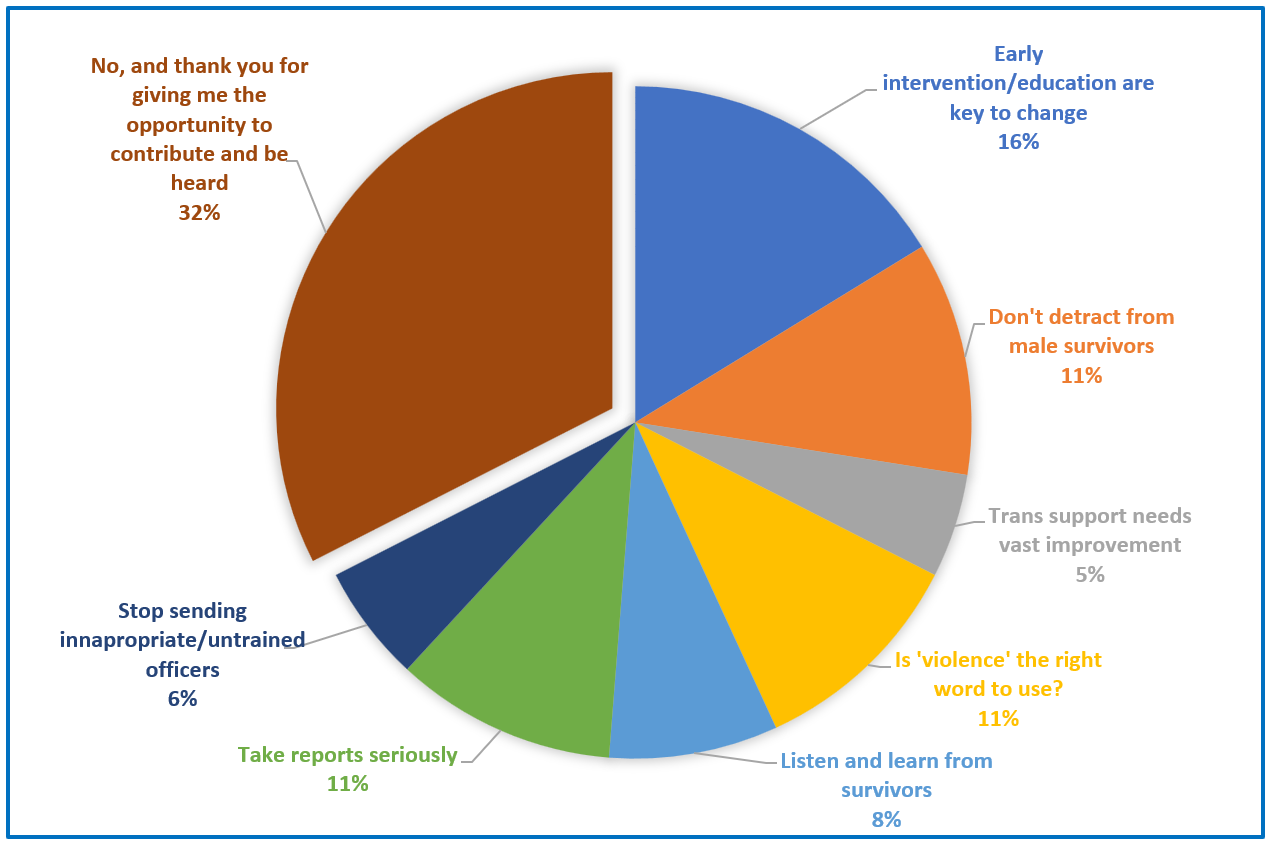

Extra space was left to add anything that those respondents wanted to tell us and are shown in figure 17, with 32% just wanting to thank us for allowing them to be heard.

Figure 17. Further points

Base: Respondents: n= 189 of 332

Question: Is there anything else that you would like to tell us about Violence Against Women and Girls?

“I think people are misled by the word ‘Violence’. They think if they don’t hit then any behaviour is acceptable”

“I feel that domestic abuse and violence is being given high profile to the outside world but is not afforded the same priority or importance within the CPS. This greatly impacts on victim’s reporting abuse and, therefore, reduces the chances of it being reduced in society.”

“Women and Girls need to be believed and be given the chance to tell their story.”

“We just need to get in there really early so that children grow up knowing what is acceptable and what isn’t and somehow putting interventions in with families if girls are not respected so patterns of behaviour just don’t keep repeating from generation to generation.”

“This is a whole society issue that starts with schools, education, and society as a whole calling it out. It won’t be tackled by enforcement alone and needs to be a truly multi agency approach including the private sector and tech companies challenging online issues.”

“I believe that young education is the main starting place for educating about violence against women. It should not be a taboo subject or something people are afraid of discussing as to ‘ not offend’ anyone. Likewise, violence against men should also be made part of the education system from a young age”

“I have had personal experience of domestic violence and I truly believe more needs to be done to educate men (who abuse women) that this is criminal, unacceptable, and extremely damaging. I believe this education needs happen in the final years of primary school.”

“Education in schools about relationships, unacceptable/acceptable behaviours, challenging stereotypes (they start young) should be part of the curriculum.”

“Education- people are often manipulated into believing they deserved or invited abuse upon them. I feel teenagers should be educated on sexual consent and abuse so that they can recognise when they are being mistreated and be empowered to report it earlier.”

“A survivor’s biggest worry is that they won’t be believed. There should be more training that is trauma informed. There should be more training about the stereotypes and myths of sexual violence and how they impact the victim. “

Conclusion

There are 4 main themes that have been consistent throughout the focus groups and survey responses, no matter what question was asked, and these will be incorporated as overarching outcomes within our local delivery plans:

1. Victims need to be heard

2. Victims need to be believed

3. Trauma aware responses should begin with the police and extend across the whole Criminal Justice System

4. Education of young people needs to be a priority to learn appropriate behaviours from an early age

VAWG Survey – April 2024 Update

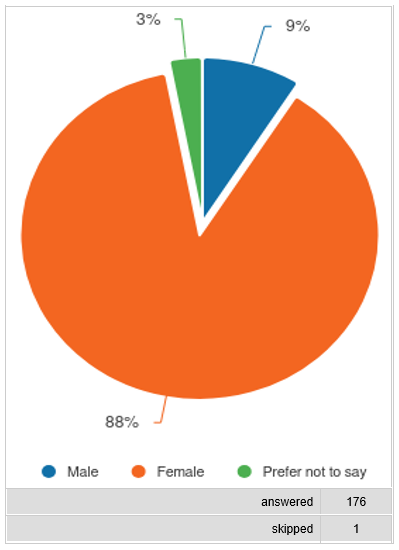

In order to ensure we continue to adopt a person-centred approach to our delivery activities, and to provide everyone the opportunity to have their views represented – every gender, every age and every situation – a new anonymous online survey was launched on 31st July 2023. Over 300 people started the survey, with 177 completing the survey in full; however this is far fewer than the 332 full responses to the initial VAWG consultation survey in March 2022 and more work is needed to promote the new survey and encourage more responses, particularly from under-represented communities and seldom heard women.

Demographic breakdown of respondents

88% of respondents were female (AFAB), and no-one identified as transgender or non-binary however one respondent skipped the sex question and two respondents choose to skip the gender identity question. This is a slightly higher proportion (+8%) of female respondents when compared to the 2022 survey.

We have seen a slight increase in the ages of respondents with 36% of all respondents aged 55 years and over, and nearly a 1/3 of all respondents aged 45 to 54 years, with only 2% aged 24 years and under and only two responses from students; this is fewer than the 12% of respondents to the 2022 survey who were aged under 24 years old.

94% of respondents identified as White, with six respondents who opted not to say and a further two respondents who choose to skip this question. 11% of respondents considered themselves to have a disability and 17% disclosed that they have a mental health condition. 13% of respondents are or have someone in their household who is a current or former serving member of the armed forces.

Respondents were asked to provide the first half of their home postcode so we can identify if there are any differing views or experiences dependent on whether they live in a more rural or urban areas; most respondents live in the Scarborough (17%) or York and the surrounding areas (17%), followed by Harrogate area (16%) or Hambleton district (16%). Only 3% of respondents live in the Craven district and 4% in the Selby area so we need to do more work to promote the survey and encourage responses from people living in these areas in particular. 12% of respondents live out of area, and 49 respondents chose to skip this question.

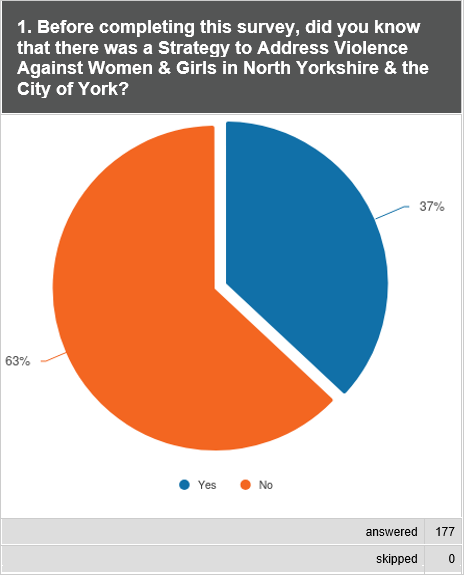

Awareness of VAWG

Only 37% of respondents were aware of the VAWG Strategy before completing this survey; consideration should be given as to whether to add a follow-up question to ask how respondents had heard about the survey if they were not aware of the Strategy.

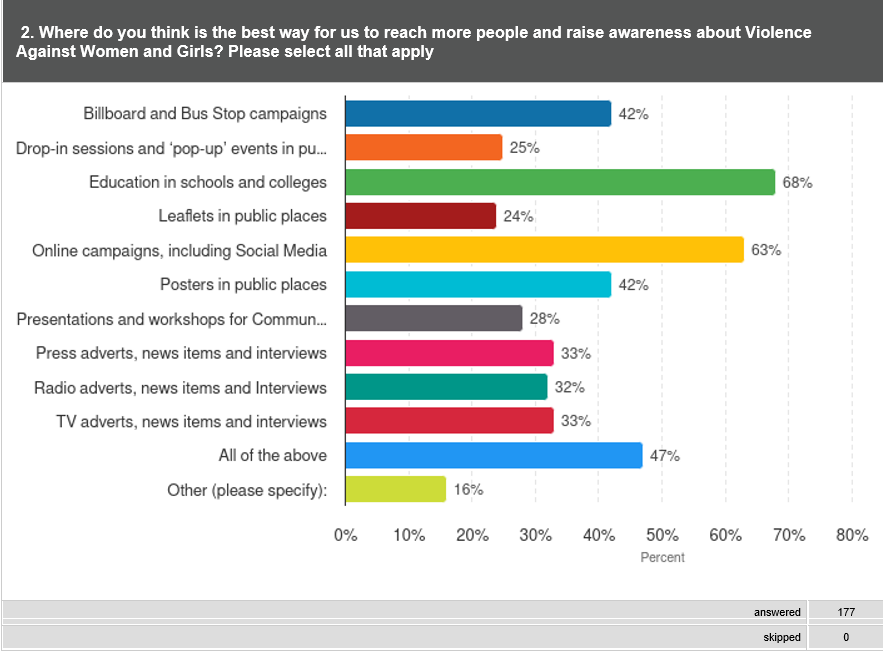

Education (68%) and awareness raising Campaigns (63%), particularly Posters in public places (42%) and Bus stop campaigns (42%) were the most popular choices for how we can reach more people to raise awareness of VAWG issues; please note that respondents could choose more than one answer to this question.

29 respondents also provided more details or ‘Other’ suggestions which again were mainly focussed on education for young people and awareness raising campaigns, both in public spaces and online. There was many suggestions stating that these campaigns should be aimed at men and boys both as potential perpetrators or as bystanders, as well as targeting male dominated workplaces, industries and sports clubs. There were also some suggestions that women and girls should also be targeted to raise awareness, both as potential victims but also potential perpetrators. Some respondents highlighted the need for any materials to be fully accessible, either in different languages and formats or key community-based locations, particularly for older or more rural communities.

113 respondents provided further suggestions of what else should specifically be done locally to tackle VAWG. The vast majority of suggestions were again focussed around greater awareness raising of the issues generally, and specifically more early prevention and education work with children and young people to encourage them to discuss these topics more openly, fostering healthy relationships from any earlier age, and preventing unhealthy attitudes and behaviours from escalating. There were many suggestions to work with parents too, particularly younger or new parents. Some respondents suggested that this needed to include more challenging and uncomfortable topics such as the impact of pornography and other sexualised or violent media content available on young people’s attitudes towards relationships and sex, as well as more online extremist views; there were suggestions that this could be better addressed by using more positive language, highlighting positive role models, both male and female, and using ‘real life’ examples of the types of abuse or violence experienced by young people to make the issue more relatable.

Training was another common theme for a wide range of professions, but the most suggested groups in need of greater training were frontline public service staff such as police, Drs and other healthcare professionals, and housing staff to ensure they are able to recognise the signs of abuse and better understand the impact of trauma on victims and survivors. Training was also suggested for those working in the night-time economy such as staff within bars, pubs and clubs but also those on public transport to help ensure people are able to travel safely home.

Physical safety improvements were also suggested by many respondents including increased and more visible police presence, CCTV and street lighting. Some respondents also suggested the need for visible and accessible physical places of safety where anyone can seek immediate help or assistance when out in public spaces, but particularly around town and city centres and public transport hubs during the evening. Many respondents highlighted the need to provide and protect gender/sex-specific spaces and services; this also included safe spaces for men and boys such as Andy’s Man Club.

In terms of increasing public confidence and trust in the criminal justice system, some respondents highlighted the ongoing impact of the murder of Sarah Everard and the need for more visible and transparent work to address inappropriate or abusive behaviours committed by police officers and staff themselves. More visible justice generally was also a common theme, with many respondents suggesting that more robust action should be taken against perpetrators, with lengthier or more severe sentencing, but also that there should be more publicity around successful prosecutions, sentencing and court outcomes.

A number of respondents suggested creating a single point of contact, helpline or contact centre for everyone to be able to access advice, help and support services more easily. Increased availability and access to specialist support services for VAWG offences were mentioned, but also more robust pathways into support for other common interdependencies such as mental health support, substance misuse, housing and finance/benefits, both for victims and perpetrators. Some respondents suggested more practical help and support should also be made available such as free personal safety or self-defence courses, particularly for young people.

Some respondents suggested more work is needed to improve partnership working and information sharing to avoid ‘agency fatigue’ and disengagement if people feel overwhelmed by the number of different agencies that are working to support them at any one time. Improved data sharing was also suggested to better map and measure the scope and scale of the issue and to ensure more effective and targeted work can take place where most needed; this would also take into consideration the key differences in the experiences of rural communities where more work could be done with local specialist charities and community organisations and groups.

Finally, use of language and terminology was raised in some responses, with the key theme of these was around the term ‘VAWG’ and some suggested that this excludes men, boys, trans and non-binary people who are also affected by these types of offences. Some respondents suggested we need to do more to ensure we are listening to all people and recognise everyone regardless of sex or gender as a potential victim of these types of offences; however there were also a number of opposing views expressed against using more inclusive language and/or providing gender neutral support and services.

Experiences of VAWG and Disclosures

Just over half of respondents (52%) disclosed that had experienced some form of VAWG offence at some point in their lives; and 66 respondents confirmed that they were happy to answer further questions around their personal experiences of reporting, disclosing and accessing support.

Positively 78% of these respondents stated that they did tell someone about what had happened to them; this is 3% higher than those who completed the initial 2022 survey. Of the 15 respondents who stated that they did not tell anyone, the most common reasons included: being unaware that it was a crime, or normalisation, minimisation and acceptance of the behaviour experienced; embarrassment and shame; thinking they would not be believed; and worrying about wider consequences such as financial, housing or work-related implications.

Positively there was slight increase in those who reported the incident to the police (38% in comparison to 30% of respondents to the 2022 survey). The main reasons for why respondents did not report to the police reflect the reasons why they did not tell anyone above, but more specifically some respondents stated they did not believe or have confidence in the police to take appropriate action, or knowing that such incidents are difficult to prove and prosecute or fear of repercussions from the perpetrator as a result. Several examples included incidents which happened 20, 30 or 40 years ago or occurred abroad. Along with general feelings of embarrassment or shame, many stated that did not want their family, friends or the wider community to know what had happened to them especially if their case went to court.

Of those who did report to the police, there were some good examples provided of positive responses from the police including: immediate action taken, specifically the arrest and removal of the perpetrator; quick and easy process to report; polite, supportive, compassionate, non-judgemental and empathetic responses from some officers; the presence of both male and female officers was appreciated; and being offered referral onto support services were also reported.

However some respondents described negative experiences when reporting to the police. Many of these included perceived negative and unsupportive attitudes of officers with some respondents describing inappropriate questions or comments such as asking them what they had done to trigger or antagonise the perpetrator, demonstrating professional complicity with perpetrators and further reducing victim trust and confidence to report further incidents. Other common issues reported were around lengthy delays and perceived slow or inaction by officers, often coupled with poor or no communication. There were also some respondents who felt that the officers demonstrated a lack of understanding of the impact of trauma on a victims, particularly around their ability to remember specific details consistently, why they may not support any further action being taken or why they remained in an abusive relationship. Some respondents reported not being offered any support until a more serious incident or substantial injury had occurred. Finally more than respondent reported being encouraged or asked to ‘drop the charges’.

Only 32% of cases progressed to court for the 25 respondents who answered this question. Of the 17 cases that did not progress to court, five respondents reported never being informed that their case would not be progressing to court; and although six reported being informed by the police, they felt that the reasons were not fully explained to them.

Of the eight cases that did progress to court, two respondents felt that the Judge and court staff were patient, compassionate and supportive; two did not have to attend court due to guilty pleas, two were heard at Civil and/or Family Court and one was heard at both a Criminal and Family Court.

Five of these respondents reported negative experiences including delays and adjournments, and lack of updates; one mentioned how formal and complicated the letters were and there was a lack of clear information to explain the process. One of these respondents also reported the significant distress they experienced immediately following conclusion of their case as they were asked to exit the court building through the main public entrance/exit and were threatened by defence witnesses; they reported that had been allowed to enter the court building through a separate entrance and felt they should have been permitted to exit through this separate entrance too.

Of the 66 respondents who were happy to answer further questions around their experiences of accessing support, 32% stated that they received some form of support from other agencies or organisations; this is slightly higher than the 28% of respondents to the 2022 survey.

A 1/3 of these respondents reported receiving counselling, including EMDR; just under a 1/3 (29%) received support through IDAS; and respondents also received support from other local support services including Survive and Kyra Women’s Aid. A couple of respondents also stated they received support through their Dr/GP or social care.

80% of those who received support reported positive experiences and outcomes as a result of the support they receive; a common theme was how helpful and empowering it was to be able to talk to someone who was empathetic, and to be given the support to work through the trauma they had experienced in a safe and caring environment.

However some respondents also reported the perceived limitations of the support available including time/session limits or inability for some forms of counselling to address the longer-term impact of trauma or more complex mental health needs. Some reported having to wait significant periods to access support and some felt that the support offer was not proactive enough, ineffective or mediocre.

Final Comments & Suggestions

Respondents were given the opportunity to share any final thoughts or comments at the ned of the survey, with 71 respondents providing further comments.

22% of these suggestions directly referenced or implied the need to challenge social norms and wider cultural change required to tackle VAWG. Some felt this is still an issue that is not taken seriously enough by some, including professionals with one respondent stating: ‘It is so “normalised” that it is very difficult to tackle. There needs to be males who will stand up and stop others when it happens and that is hard to do.’

Further to this, 9% of respondents directly raised the issues created or amplified through social media and online content. Some specifically spoke about the challenges of increasingly extremist views being shared online; one respondent suggested developing a similar approach to VAWG and misogyny as the PREVENT method.

Another linked theme raised by a number of respondents was the need to challenge the use of victim blaming language, both at an institutional level but also at a wider societal level, and to shift the onus from women and girls to keep themselves safe onto challenging those who are committing these offences against them.

Around 21% of comments referenced the use of language and terminology connected to gender and sex; around half of these were in relation to the difference between biological sex and gender identity and the need for sex-specific safe spaces for females. The majority of the remaining comments were around the need to recognise men and boys as victims too, and women as perpetrators; however, one respondent stated that they appreciated the trans- and gender-inclusivity of the language used.

The next most common theme, referenced in 20% of suggestions, was focussed on the need for more awareness raising campaigns, education, prevention and early interventions including through the use of specialist support services to address contributory factors such as mental health and substance misuse support services.

Around 15% of comments referenced the police and/or wider criminal justice system, including many which called for more visible police presence in the community and more training for police officers to challenge inappropriate attitudes and support them to ‘be a beacon of good practice’. Around half of these respondents also referenced the perception that the justice system has ‘gone soft’ on theses perpetrators and concerns around low conviction rates generally.

More specific suggestions were submitted around the need for more specialist support for female offenders, particularly those who are involved with the criminal justice system because of the abuse, exploitation or coercion they have experienced. A further comment raised concerns some women have that they will be criminalised if they defend themselves.

One respondent disclosed their fears and feelings of vulnerability as a lone female travelling or visiting places alone, particularly at night; they suggested that we should look to provide physical safe spaces or specific safety points with a direct line to help or support.

Three respondents raised the issues faced in rural and isolated communities, including our market towns; specifically that much of the issue remains hidden and victims are afraid to ask for help so there is a need for more outreach to address this.

Finally, a couple of respondents ask that we engage directly with victims and survivors to be able to fully understand their experiences and the impact of years of abuse longer-term.