Stop Hate Crime – Race

WARNING:

This report contains offensive language. These are examples of hate crime that were expressed over the course of this research. This language has not been censored as it is important to understand the nature of this type of crime as it occurs.

Translate this page

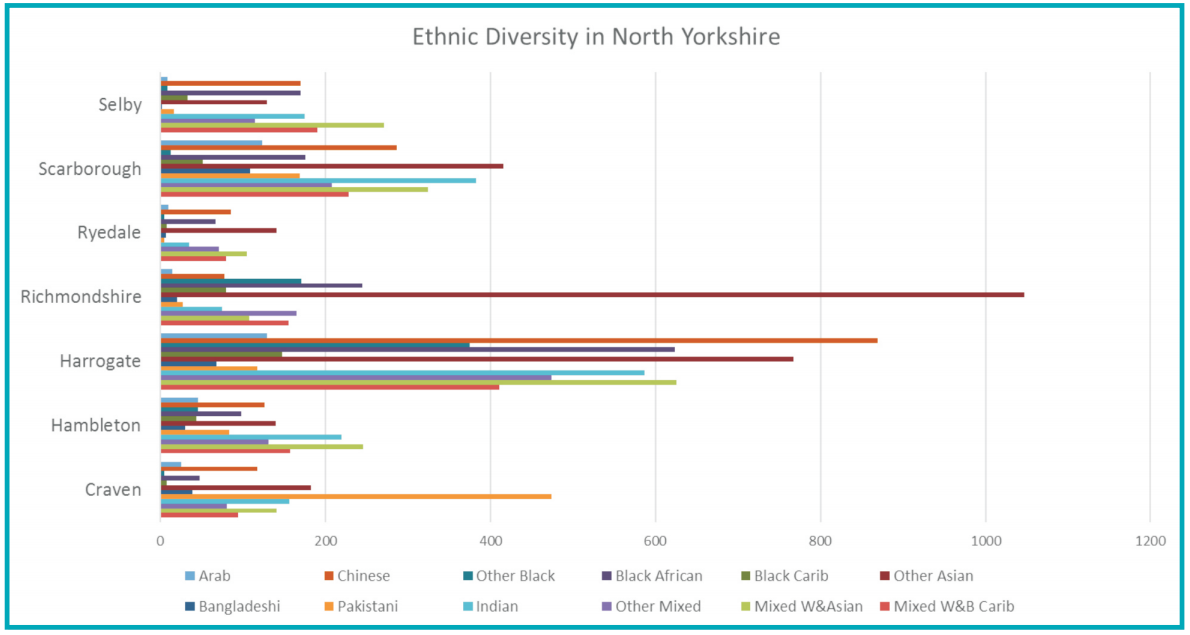

Census data shows that the social make-up of North Yorkshire is not particularly ethnically diverse, but that there are pockets of ethnicity throughout the area. North Yorkshire has a very high white British ethnic population at 93.4% (80% nationally; 88% in South Yorkshire; 78% in West Yorkshire and 85% in Humberside), meaning that non-white communities are likely to be very small (over 1000 people in the largest non-white ethnic group, in Richmondshire).

York, Harrogate and Scarborough have the highest population densities, meaning that the majority of diverse populations are located in these areas. However, some less populous areas have specific diversity patterns (see below).

- Within the ethnic communities of North Yorkshire, Richmondshire has a high proportion of people of ‘other Asian’ ethnicity (21.8%). This is mainly due to the Ghurkha population at Catterick Garrison

- Richmondshire also has the highest ‘other Black’ population after Harrogate at 24%. Again, this could be attributed to the diversity at Catterick Garrison and nearby towns

- Selby and Hambleton have significant proportions of White Gypsies (18.4% and 15%)

- Craven has a significant Pakistani community, with the highest proportion of Pakistanis in the whole county at 36%

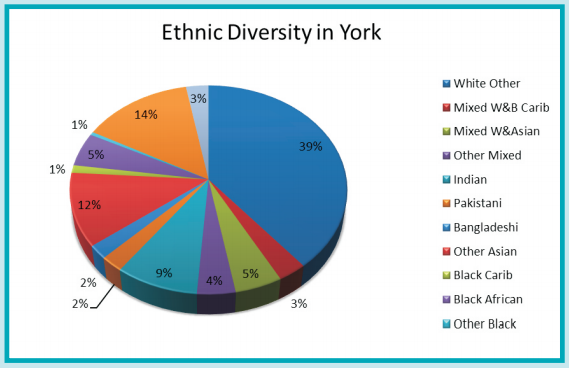

- York, as a densely populated area, has a large Indian community, accounting for 48% of the entire Indian population of the whole area[1]

The City of York is the most populous area and has the most diverse makeup. The chart below shows diversity in York, excluding white British and white Irish.

The predominantly white British demographic might mean that race hate crime is more prevalent than other hate crimes because ethnic differences (i.e. individuals who are non-white) are more obvious in a less diverse setting (hypothesis 3).

It may also mean that there is less tolerance of racism: it is not viewed by the general populous as a societal norm, so it is more likely to be reported to the police by victims (hypothesis 4). In turn, this might suggest that non-white communities have a stable relationship with the police as there is a willingness to report race hate crime.

In terms of racial hatred, derogatory racial slurs are seen most often, with abusive language.

Understanding of hate crime

- What does ‘hate crime’ mean?

All respondents who participated in the focus groups from a diverse racial background were able to identify what a hate crime is: ‘bullying…because of the way we look.’ However there was uncertainty around whether name calling or non-physical methods were actually criminal. In some conversations there was a sense of embarrassment from individuals who had shrugged off verbal incidents of hate, suggesting that it ‘wasn’t important.’

Many felt that hate crime was not serious enough to report to the police – they suggested that if there was a physical element (assault), then they would get in touch with the police, but didn’t feel that ‘just bullying’ was a crime. For those individuals who had stronger community links, such as students or members of active organisations, there was a strong sense of social motivation.

On the whole, the Ghurkha community (especially adult men, those at the top of the structural hierarchy), does not experience problems with crime (that are expressed to the police). However, others in the community, particularly young people, can be victims.

- Young female students at a local interfaith school have been victims of school bullying including abusive and derogatory name calling; mock imitation of accents and even assaults: ‘[She] gets bullied at school… they imitate her accent because she doesn’t speak good English’

Younger people in the Nepalese community did not recognise hate crime as criminal, perhaps due to language barriers or consistency of abuse. The teenagers expressed very strong feelings of pride in their background, ‘we’re Ghurkhas – we help them out,’ which may be an internalised barrier to reporting.

Relationship with the Police

- What is your attitude to the police generally?

- Did you report hate crime? Why/why not?

- How did the police respond to you? How did they treat you? What was your opinion of the officer that dealt with the crime?

Overall, there was a good understanding of how to get in touch with the police if there was an emergency (via 999), and many felt that they would contact the police if the crime was severe. Generational differences would mean that older people might report crimes that were very serious, whereas younger people might be more willing to report lower level crime. However, some expressed a lack of understanding of police processes more broadly (i.e., what happens when I report a crime?) and for those who had reported previously, there was dissatisfaction around the lack of feedback mechanisms that are in place when a crime (any crime) is reported. There was a high level of uncertainty around reporting hate crime specifically due to possible repercussions of having ‘told’ to the police and the potential for abuse to escalate.

‘They keep it to themselves because they’re scared of what is going to happen.’

‘I’ve never met a police officer.’

‘They’re worried about what is going to happen after they have involved the police.’

Others did report to the police, but understood that the nature of the crime might mean that the police are unable to act, particularly if the incident was random or the victim didn’t have thorough details. Some felt that they ‘just had to tell someone’ even if they knew the police couldn’t take the case further.

Some communities, particularly those in Catterick, were happy to ‘keep themselves to themselves,’ and often had no relationship with the police. The younger people in the Nepalese community suggested that they would ‘ask why [the offender] treated them that way’ and would only go to the police if it was ‘really bad’ or ‘constant.’ They didn’t feel that name calling was enough to justify police involvement and that there had to be some perceived criminal or physical element.

Perceptions of the police more broadly focused on negative news, particularly ‘institutional racism.’ Although not specific to NYP, some individuals felt that this rhetoric damaged police/public relationships and made racial groups more wary of the police. They felt it was the responsibility of local forces to turn this negativity around by engaging better with minority communities. Many expressed that they did not expect the police to be experts in all cultures, but felt that the police should be confident to ask questions to develop their personal understanding and ensure that the needs of the individual are met appropriately.

Some diverse and often hidden or hard to reach communities, such as the Nepalese and Fijian populations across North Yorkshire, fall under the radar of the police and other services. Arguably there is little awareness of hate crime as a form of abuse and probably even less awareness of available services and support mechanisms.

Some suggested that the police would try to ‘brush off’ race hate crime, which then deters victims from reporting in the future. One participant described having racial abuse shouted at him in York city centre – the police asked him if he ‘really wanted to report this as a crime, or just go your separate ways… I had the feeling they just weren’t interested because there are other things they’d rather be dealing with on a Friday night.’

Others expressed that police appeared unprepared for dealing with hate crime and that when it was reported there was little support, regardless of whether or not the crime could be ‘solved.’

‘There was no mention of any services that can provide support or anything.’

‘It was an unsupportive experience, I don’t know how that case progressed… It has put me off, totally [from reporting to the police in future].’

The ‘normality’ of hate crime

- Do you feel like you are treated differently because of any real or perceived difference between you and others? Is this a ‘norm’?

- If you became a victim of hate crime, what would you do?

There is a lack of understanding of culture and race between different communities – this is not shown through racism necessarily, but to some extent, the separation of communities. The Nepalese group said that a wider community day to help others learn about their culture would be beneficial to ‘break down’ any barriers or misconceptions.

‘Sometimes, people think we don’t speak English.’

‘Some people think, ‘why is this person here if they can’t even speak our language? That can cause an argument.’

Some suggested that the colour of their skin meant that people would assume things about them, such as language or religion. They felt that this was a barrier that would continue to exist until different groups learned about each other.

Other expressed that racism was historical and that victims of abuse 20 years ago remained internalised and ‘kept themselves to themselves’ to avoid any further crime. The lack of integration of some Black and Pakistani communities meant that isolation from others and from services could be a prevalent issue. Minorities can easily become isolated and insular when they become victims in their own community, reducing the likelihood to speak out about hate crime:

‘We would have excrement thrown at our back window and bottles thrown into our yard. It was very sporadic. You lose trust in people, in your community because you don’t know who is involved.’

‘You don’t know who is doing it, you don’t know if it’s that person you’re talking to.’

National and international events have fueled intolerance towards Middle Eastern and Indian subcontinental ethnicities. The Rotherham child sexual exploitation scandal raised questions about the Asian-Pakistani men involved and the perceived lack of police involvement; The conflict in Syria, the increasing prevalence of Islamic State (IS) and events such as the shootings in Paris and Canada have been well established and reported in the media.

Events such as these can be incorrectly interpreted as a ‘norm’ or accepted fact or representation of different races, faiths or ethnicities, fueling racism. These generalisations and misconceptions turn into hate, aimed at people to intimidate and threaten. British Pakistanis and other Asian minorities accepted that they would be victims of abuse until these representations changed.

The British Pakistani and Nepalese focus groups highlighted a change over time in the type of words that were used against them. A group of British Pakistani Muslim women said that when they were growing up, they would be called ‘Pakis,’ but that they rarely hear this word now. Instead, they hear ‘terrorist.’ They noted that the hate had moved away from their race, and towards their religion.

Some younger respondents from the Nepalese, British Pakistani and Black communities felt that their reluctance in reporting came from an internal unwillingness to accept that they had become a ‘victim’ of a crime. Some said it was easier to ‘just get on with it’ and that in some cases, the certainty of abuse was so rife, that reporting crime would take too much personal time and effort. There is a high consistency of abuse in some of these communities due to the incessant nature of verbal abuse over many years – they have simply ‘got used to it.’

The majority of race incidents reported to NYP are from people who work in the Night Time Economy (NTE), such as taxi drivers, restaurant/takeaway employees and door and security staff. There is an established relationship between police and NTE staff, as victims are more willing to report hate crime, however, preventive measures should be taken to find the causes of hate in the NTE. As with NTE-related crime more generally, alcohol is likely to be a contributory factor in raising aggression and lowering tolerance, suggesting that more action could be taken proactively to raise awareness of racism.

Conclusion: racism is happening in North Yorkshire

The groups involved in this research explained that racism remains a prevalent issue. Although NYP figures show that racism is more widely reported that other forms of hate crime, the discussions for this research suggest that this is only a snapshot of the reality. By way of a summary, each of the original hypotheses will be addressed in turn against the gathered evidence from focus groups.

- Diverse groups have no relationship with the police in North Yorkshire and York

Some groups do have an established relationship: the Pakistani community in Skipton in particular has a good rapport with local officers. Others were very insular and did not engage with services, such as the diverse groups in Catterick. For some however, historical racism in policing was seen to be a barrier and created mistrust of the service. Older people across all ethnicities were far less likely to report perceived ‘less serious’ hate crime. They had good understandings and expectations of the police, but would only make contact if there was more serious crime such as criminal damage.

- There are barriers to reporting hate crime

Language barriers and lack of awareness of services and support were common themes. An inability to communicate with the police or feelings of isolation within communities means that victims do not come forward. Community Mentors at York Racial Equality Network (YREN) (who have a role to support their communities and educate about hate crime) were the only individuals out of 17 groups to have an awareness of Stop Hate UK in North Yorkshire, or the services provided by Supporting Victims.

- Victims become victims because they are different in some way

Race and misconceptions about race are prevalent. International events and news ‘tar everyone with the same brush’ who looks similar, and learned, social behaviour still exists. North Yorkshire and York is predominantly ethnically white – those non-white communities therefore are comparatively very small and in isolation, perhaps becoming ‘easy targets.’

- There is an established ‘norm’

Due to social exclusion or isolation of minority communities, there is an indication that those who are excluded can become targets. Older people felt in particular that they were more likely to be victims, based on historical experience. However, this was not shown across the board: for British Pakistanis in particular, perceived characteristics of their minority, based on global events was an indicator for changes in attitudes. A comparison in more ethnically diverse areas (such as West Yorkshire, for example) may be a good indicator of how ‘normal’ or frequent race hate crime is in North Yorkshire.

- There is a heightened sensitivity to hate crime

More victims of race hate crime reported to the police, suggesting that there is more awareness of this type of hate crime compared to others. Racism on the whole is understood to be unacceptable in society.

- Police response to hate crime is poor

Some suggested that support mechanisms were not widely known about and others had suffered bad experiences. However, on the whole, most felt that the nature of hate crime meant that there could not be a positive outcome (in terms of solving the crime), but that this was a frustration shared by both the victim and the police, rather than a fault of the police.

[1] Office for National Statistics, ‘Ethnicity and National Identity in England and Wales,’ 2011